A commit story

Week 3: Jan 11 - Jan 18, 2026Programming is hard.

This week has proved that. It has made me feel terribly unfit, as if I was part of the January crowd struggling up the stair masters at the gym. My mind has desiccated. It is less limber, less able to reason about complexity and solve problems quickly.

Mikkel often says that he hit his mental peak when he was 12. That statement only ever drew my skepticism, but I do lend it some credence now. We’re old — and compared to the us from ten years ago who spent our lives living in our IDEs, we’re worse programmers now.

It is strange how our careers work. We spend our youths studying: trying incredibly hard to learn concepts and challenge our fundamental understanding of the world. We develop a level of mental acuity that is near impossible to replicate, and tout it in competition with exam scores and math contests. Then we join industry, acclimate for a few years, find a position of comfort, and gradually waste away as a bunch of political potatoes.

Tangent aside, this week was alright.

It could’ve been better, it could’ve been worse, but it was a reminder nonetheless to humility: that we have much to learn and grow yet.

Commits were the focus.

A commit is a diff. It is a set of change operations done on a set of files. It is also a log. It has semantic meaning, each commit typically indicates some logical unit of work. And finally, commits are chronological. A commit is a point in time, and a collection of commits comprise a commit history: a record of work done.

Commit history is the single GitHub feature I use the most.

Opening up my browser, typing in our repository URL, and then clicking “history” and catching up on Mikkel’s late-night commits is part of my morning routine. That is likely a bit unique to the ways in which we work as an early stage startup, where we tend to just push code rather than open pull requests, but commit history serves several functions that are more universal to developers.

When looking at a new repository, it is often easier to scan through recent commits than it is to read the code from scratch. In fact, I’d argue that most new visitors tend to not read the code at all and often only skim the README, documentation, and commit history. You can gleam quite a bit from just that alone: even though you may not build a complete understanding of the codebase, you can understand 1) whether the repository is actively maintained or not, 2) the sorts of recents changes under development, and 3) the contributors doing the work.

Furthermore, a commit is an incredible tool for learning.

A commit is an example of how to do work in a repository. If you’re a new engineer and you’ve been tasked with the unglamorous work of fixing a flaky CI build, your first impulse should be to see if similar fixes were done in the past (and if so, copy and paste).

Conversely, commits also stand as a representation of an individual. Few things make engineers happier than seeing their commit history be littered with green. And it also serves the undeniably less fun function of resume-building and engineering performance reviews.

There’s more that commits do. They solve the rare, but salient problem of change association: figuring out what changed in a given timeframe. When things break in prod and you don’t have a clue as to why, but do know when things stopped working, rifling through recent commits is often your first recourse. Commits are also a simple tool for development — I often find myself using GitHub to fetch some prior version of code that I now need reference to.

That is all to say, commits are important.

We think it is one of the most important features of GitHub, and one we should take particular care to do well.

Commits are quite hard to build.

The data modeling itself is not so difficult, commits are fundamentally a chronological list of often spurious commit messages and SHAs.

The design is interesting. Due to the chronological nature of commits, there’s many ways you can go about representing them (e.g., flame graph, weekly planners, even calendar-based designs), but while open-ended, is the kind of thing where diligent exploration and exercising restraint leads to reasonable results.

What’s difficult about commits is diffs.

Diffs are quite the complex piece of software.

There’s several ways to implement diffs.

The most common, and the one that git uses by default, is the Myers algorithm paper.

To illustrate, say that you have the following two strings:

KITTEN

SITTING

A valid diff would be:

- K

+ S

I

T

T

- E

+ I

N

+ G

The above representation is an edit script, where at each line we either add a character, remove a character, or match characters.

The goal of Myers is to generate the shortest edit script possible.

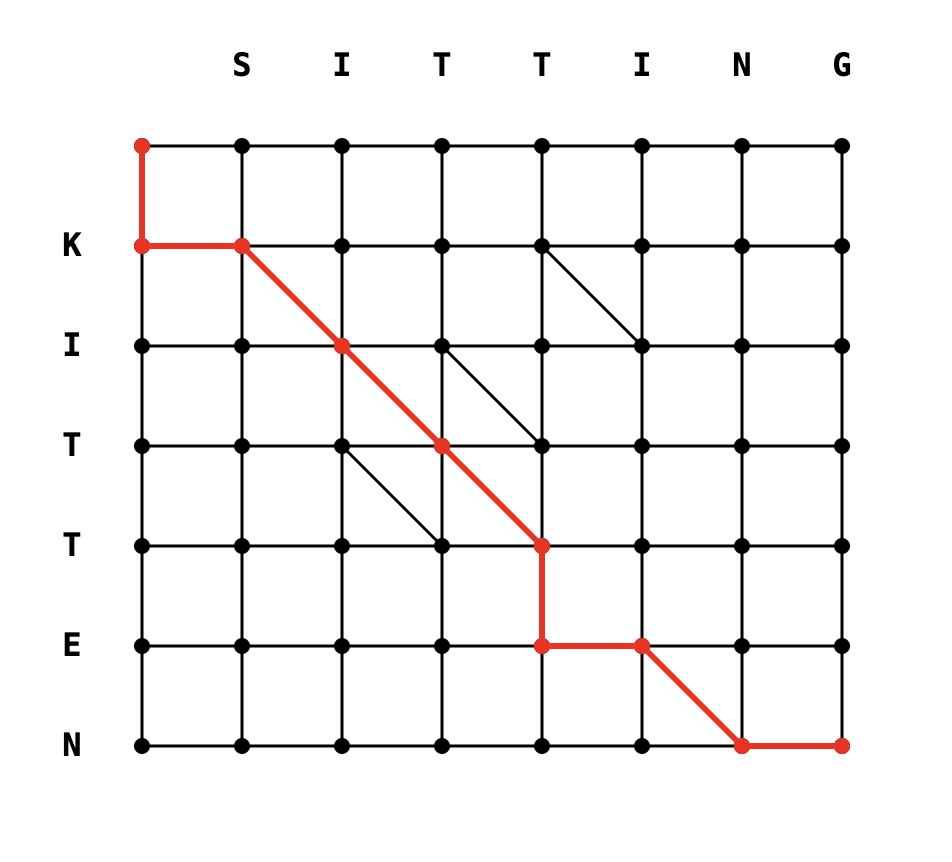

We do this by first constructing an N x M grid:

At each node, we have the following options:

- Go down — delete the character below

- Go right — add the character to the right

- Go diagonal — if the node below and the node to the right are the same, match characters

So rather naively, you can see a typical dynamic programming approach where we retain the minimum cost path of each vertex, giving a time-space complexity of O(NM).

Myers' does better by exploiting the structure of the problem: since diagonals are free, greedily follow matching characters as far as possible before making the next edit. Likewise, there's never a reason to track anything on a diagonal but the farthest point reached with d edits. So by iterating through d = 0, 1, 2, ... in a breadth-first search and only exploring diagonals reachable with exactly d edits, Myers achieves O(ND) time complexity.

Before we talk about other diff algorithms, it’s worth establishing that there are often many valid diffs for a given pair of strings. For example, rather than remove K first and then add S in the example above, we could’ve done the opposite: add S and then remove K.

This is particularly important for code, where the choice of what diff to render directly affects the user experience:

class Foo class Foo

def initialize(name) def initialize(name)

@name = name @name = name

end + end

+ +

+ def inspect + def inspect

+ @name + @name

+ end end

end end

Myer’s algorithm is fast and tends to produce diffs that are good quality (i.e., readable) most of the time, but there’s a few failure cases that are particularly bad for it (i.e., aligning braces).

A few attempts to improve upon the algorithm are recorded in git’s history.

The patience algorithm was created by Bram Cohen, the author of BitTorrent.

In his words, the algorithm works as follows:

- Match the first lines of both if they're identical, then match the second, third, etc. until a pair doesn't match.

- Match the last lines of both if they're identical, then match the next to last, second to last, etc. until a pair doesn't match.

- Find all lines which occur exactly once on both sides, then do longest common subsequence on those lines, matching them up.

- Do steps 1-2 on each section between matched lines

Note that this still uses Myers’ under the hood to do the longest common subsequence, but the heuristic here is to favor unique common lines and match them up, which discredits syntax-only lines like brackets.

There’s another extension upon the patience algorithm known as histogram diffs, which uses lowest occurrence elements as a fallback in case there are no unique common lines between elements. But I will say that the difference between the two is quite minute.

There’s been a few recent attempts to build better diffs.

The main one to talk about is difftastic, which is centered around the notion of AST-based diffing. Rather than treat the problem of diffs as one of strings, parse each file as an abstract syntax tree and treat it as a shortest path problem.

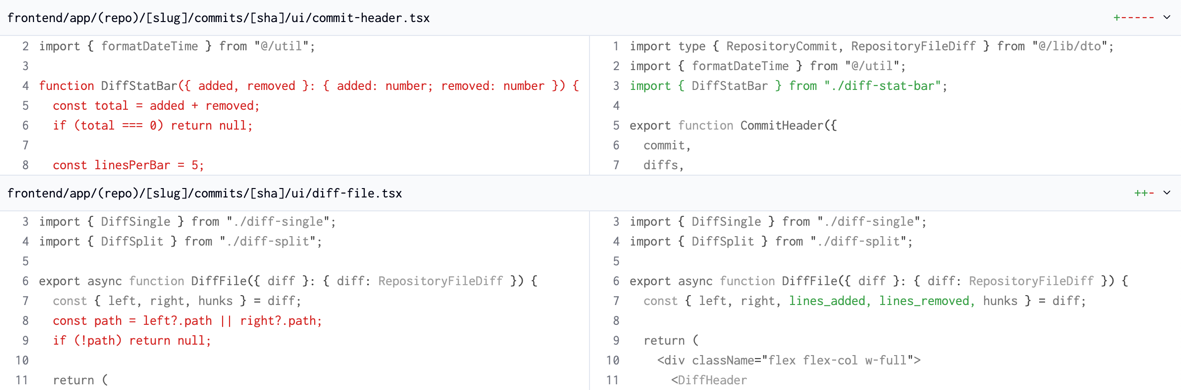

The benefit of AST-based diffing is that you’re now able to do word-level highlighting.

And while you can technically achieve that by augmenting traditional diffing algorithms with Levenshtein heuristics, AST-based diffs give you a stronger guarantee.

It lets you say front and center, that this word is the one that has been changed.

That means instead of things like this:

We can do things like this:

We recognize that this looks a bit strange in a world where we’re used to our code in color, but do think it has merit.

If the function of a diff is to identify what has changed, it is hard to argue against the sheer simplicity of showing removals in red and additions in green.

The actual implementation of what you see above is quite involved.

difftastic is a CLI tool built in Rust, meaning that there are no public APIs. While we debated forking the library (and do think it likely necessary in the future), we chose to invoke the CLI as a process with the experimental display --json flag and parse the output instead.

That was difficult as that output is only a subset of the information that difftastic acquires. It only returns the absolute bare minimum: what lines were removed on the left, what lines were added on the right, and what lines were modified. It excludes the filler lines in between, meaning that we have to implement heuristics as to guess the “right locations” to insert padding lines.

There’s also quite a lot of front-end complexity with diff viewers.

Syntax highlighting is already complicated (DOM trees with thousands of spans with different styling), but that gets exacerbated with a side-by-side view and the modern features we're accustomed to: line-range highlighting, code hunk expansions, and commenting.

And finally difftastic can also be quite slow, which means that we had to employ a two-tiered suspense paradigm to stream content gradually for latent pages, but also avoid showing a loading indicator for pages that load quickly.

Outside of that, Mikkel got into a biking accident.

Luckily it wasn’t too serious, though I’m sure was certainly painful, and is a reminder to us all to wear helmets and avoid icy roads.

As for his work, he spent this week implementing domain-driven design within our Rust backend, which I currently understand to be a Java Spring inspired separation-of-concerns architecture and also did the hard work to setup our infrastructure, authentication, and deployments.

He and I do tend to work incredibly independently, so I must admit, I can’t write to his work with the same detail that I do mine, but regardless, I’ll continue to find a way to record it here.

Thank you for reading

—baepaul.